I wrote this article in Japanese and translated it into English using ChatGPT. I also used ChatGPT to create the English article title. I did my best to correct any translation mistakes, but please let me know if you find any errors. By the way, I did not use ChatGPT when writing the Japanese article. The entire article was written from scratch by me, Saikawa Goto.

Introduction

Movies and books covered in this article

Three takeaways from this article

- The two projects that I felt were amazing at the Mori Art Museum exhibition.

- About Chim↑Pom’s main theme of “public.”

- Who is Chim↑Pom to begin with?

Self-introduction article

Published Kindle books(Free on Kindle Unlimited)

“The genius Einstein: An easy-to-understand book about interesting science advances that is not too simple based on his life and discoveries: Theory of Relativity, Cosmology and Quantum Theory”

“Why is “lack of imagination” called “communication skills”?: Japanese-specific”negative” communication”

The quotes in the article were translated using ChatGPT from Japanese books, and are not direct quotes from the foreign language original books, even if they exist.

I Went to See the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition: Happy Spring” at the Mori Art Museum Without Knowing Much about Chim↑Pom, and it was Amazing

The “Chim↑Pom Exhibition: Happy Spring” was held at the Mori Art Museum from February 18, 2022 to May 29, 2022.

The other day, I went to see an exhibition that was so stimulating it blew my mind, and I was thrilled. Although I am not very familiar with art, I occasionally visit art exhibitions. While I have seen quite a few art exhibitions in the past, this “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” was by far the best. I can confidently say it was the most impactful one I have ever seen.

I have never written any articlres about an art exhibition before. While I always write something about books or movies, I couldn’t write about art exhibitions. As a matter of course, because most art exhibitions stimulate the “visual” senses, and I couldn’t express it in words.

However, at the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition,” I was constantly stimulated to “think.” That is why, unlike usual, I can “verbalize” it.

After I went to see the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition”, I found out that there would be a special feature on Chim↑Pom in the April 2022 issue of “Bijutsutecho” magazine, so I bought it for the first time. By reading it thoroughly, I feel like I was able to organize my thoughts on Chim↑Pom to some extent, which I had known nothing about before.

In this article, based on the exhibition at the Mori Art Museum and the descriptions in “Bijutsutecho”, I would like to develop an article centered around the “public” theme that Chim↑Pom often focuses on.

In “Bijutsutecho,” there are interviews with various people who have experience working with Chim↑Pom as organizers (external collaborators). One of them is the curator Tazuke Nana, who speaks like this:

”I think the overall dynamics of Chim↑Pom’s project is very sustainable. Rather than simply being inspired by social phenomena and creating works related to them, they connect the concept of the work to the real society and physically intervene themselves. They are starting from the society we actually live in and trying to find the “street” that leads to the future while connecting it to where they are. It’s very interesting that they sometimes express social issues with irony and humor.”(Tazuke Nana)

”Chim↑Pom plays a role in exploring areas that are considered taboo.(omission) I believe that they are a bridge that connects the two in the sense that they “question established frameworks and connect the public with what is considered to be high art”. (Tazuke Nana)

The fact that art can play a role in exposing “social issues” is generally recognized, and Chim↑Pom takes it a step further by posing questions to the “public.” Even the Mori Art Museum exhibition, the artwork that struck me the most was precisely about the essence of “public” and its significance, with a simple and vivid concept that left me in awe.

This is not limited to art, but I believe one of the values of experiencing various things and values in the world is the opportunity to think about things that we don’t usually think about. It’s rare to think about the “public” unless it conflicts with power or laws, but encountering Chim↑Pom’s artwork would naturally generate questions in our minds. I felt that the ‘presence as an art piece’ and the “vividness in questioning social issues” coexisted remarkably, and it was an exhibition that made me consider adopting a similar stance as Chim↑Pom in my own area of expertise outside of art.

It is truly an overly stimulating art exhibition full of “values and sensations that are essential to daily life but not available in everyday life.

Then first, let’s take a look at the two exhibitions that struck me at the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” at Mori Art Museum, taking into account the description of “Bijutsutecho”.

The Impact of “Street” that Connects “Inside” and “Outside” at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts with Asphalt Road

At the Chim↑Pom Exhibition, taking advantage of the “circumnavigable structure” of Mori Art Museum, it is guided that it can be viewed from both clockwise and counterclockwise directions. Although most people would typically follow the clockwise, the first space that appears in that case is a low-ceiling space with scaffolding like those seen at construction sites. The excitement begins from the start where a completely different “scaffolding from a construction site” exists in the high-class space of Mori Art Museum.

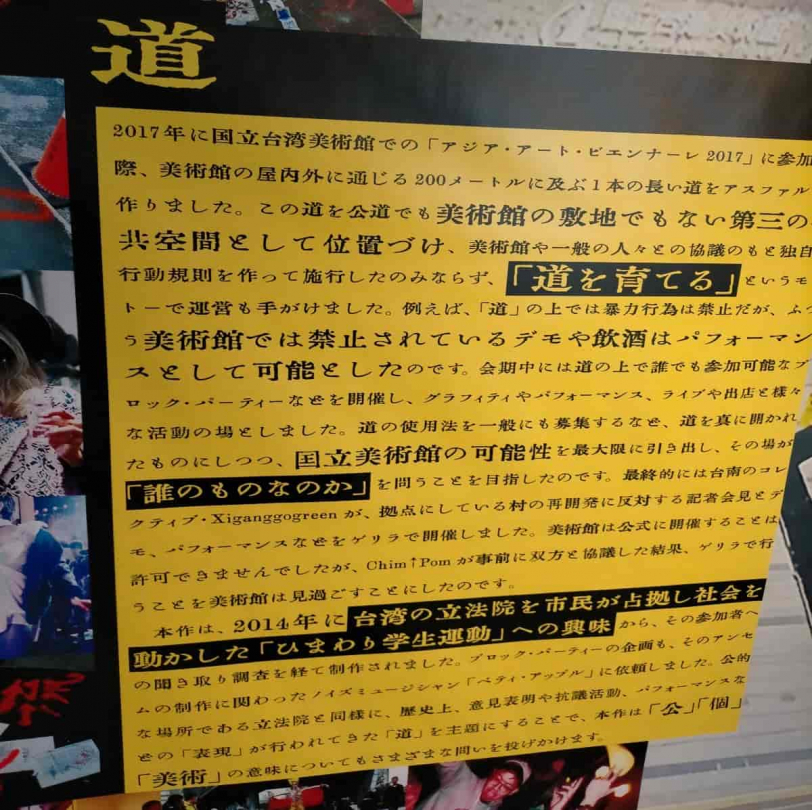

There, many exhibitions from various projects Chim↑Pom has done in the past with themes of “city” and “public” were displayed, including the project “Street” that took place at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts for nearly half a year.

I was truly shocked by this “Street”.

Simply put, it can be described as “a road of asphalt” connecting from the public road in front of the museum, passing through the museum’s parking lot, and all the way to the museum entrance.

What’s so amazing about it? It is tha point that the content raises questions about “publicness in the museum” and “publicness on the public street.

The term “public space” can mean a variety of things. Common areas of condominiums, libraries, city halls and community centers, shrines and temples, hospitals, etc., may come to mind as a variety of spaces that one feels comfortable calling “public space. However, the rules and regulations for what is allowed or not allowed in each place may vary. And we often take these rules for granted and accept them as the norm without consciously considering them.

Chim↑Pom used this simple exhibit of “laying asphalt on the road” to vividly illustrate the difference in “publicness.”

The “question” presented to the audience through this exhibition is as follows:

Is there a difference between what can be done in an art museum and what can be done on the “public road” inside the art museum?

To better understand this point, let’s quote the description of “Street” written in “Bijutsutecho.”

Even in the same public space, there are different rules between the public road and inside the art museum. Chim↑Pom has set up “regulations” that apply only to the “Street” that connects the two. Through negotiations with the museum, they define all activities that take place on the “Street” as part of the artwork, allowing graffiti and eating, which are normally prohibited. Demonstrations are also allowed only if organized by Chim↑Pom. While acts of violence and public obscenity are not allowed, “romantic and loving acts” are allowed freely.

When it comes to graffiti or eating, it’s not something we can do in a museum. However, it might be allowed on a “public road” (graffiti is still a bit of a gray area though). So what about on a “public road” that exists within the museum? This would be definitely a question that nobody has ever thought of before. That’s because there’s no necessity. But through this exhibition, we can become aware of the “difference in publicness” that we usually accept without question.

I myself was prompted to think about the “difference in publicness” by encountering this exhibition about the “Street” (and its explanation). It means that it made me look at an area that I wouldn’t normally question.

Moreover, this exhibit highlights the cultural differences between countries.

For instance, even in terms of occupying roads, there are significant cultural differences between Japan and Taiwan.(omission)

In Taiwan, it is common for roads to be temporarily occupied for events such as weddings, funerals, and festivals. On the other hand, people in Taiwan are accustomed to religious activities and banquets on the streets, but they tend to show resistance to techno music and parties, indicating a clear double standard. “(omission) Parties are also part of social structure, reflecting the current society like a mirror.”

In Japan, roads may be closed during festivals and other events, but it’s not common to see roads being occupied for weddings or funerals. Taiwan, on the other hand, seems to have a higher tolerance for road occupation during such events. However, even in Taiwan, parties are not tolerated. It’s definitely a double standard. By focusing on the “difference in public nature,” we can also reflect on the societal norms.

In a discussion about “public” in Bijutsutecho, Ushiro Ryuta from Chim↑Pom made the following remark:

”In the West, there is a concept that public property is owned collectively by everyone, and limiting individual rights to create something together. This creates a sense of ownership and responsibility. On the other hand, in Japan, the public is perceived as something like wilderness or the sea, just there to be used without a sense of ownership”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

The exhibition of “Street” was held in Taiwan, which is also in the same Asian region as Japan. If the same exhibition were held in Europe or the United States, the reactions might be different. This simple method of “laying asphalt roads” brings to light various values that are not usually consciously recognized. Just being able to know about the existence of “Street” makes me feel glad that I saw the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition”.

Earlier, I mentioned that “parties” on the streets in Taiwan are met with resistance, but during the exhibition period, actual parties were held on “Street” at Taiwanese art museums. Betty Apple, who was involved in curating the “Street” party, had this to say.

The biggest challenge was providing food and drinks, especially alcohol. “Parties have an element of wild excitement. It’s similar to theater, but it’s not just about escaping reality, it embodies the relationship between ‘art and freedom.’ That’s why I think alcohol is necessary, but that was the most difficult part this time. We negotiated persistently with the museum, centered around Chim↑Pom, and got permission to include food and drinks as part of the artwork, but alcohol was absolutely impossible.” Since permission was not granted until the end, they basically went outside to drink on the lawn and then returned indoors to dance, repeating the process. “Other times, the volume was suddenly turned down on its own, saying that a complaint has been received. There were times when I thought we had no choice but to cancel.” We repeated negotiations each time, and the party ended successfully without any issues.

“Doing a party inside an art museum” would normally be impossible, but by adding the element of “public road,” it became something that could exist as a realistic solution. This kind of thinking could be a reference as one of the breakthroughs in various situations that have reached the point of “it’s impossible anymore.” It means that there is magic that can change something that is normally impossible into something that is possible.

About Betty Apple, it says:

”I have always had a strong interest in Chim↑Pom’s activities through news reports and other media. I was particularly sympathetic to a group of works related to the nuclear power plant accident that were exhibited at a gallery in Taipei in 2012”. (Betty Apple)

It seems that Betty Apple’s participation in the “Sunflower Movement” demonstration in Taiwan afterwards became the catalyst for teaming up with Chim↑Pom for “streets”.

”I felt that I could share the idea of ‘liberating the body in public spaces’ with Chim↑Pom”. (Betty Apple)

”Both Chim↑Pom and I, as artists, have been considering the meaning of parties. What I find impressive about Chim↑Pom is how they connect this with social structures and have very clear issues”. (Betty Apple)

She speaks like this, and I agree. Chim↑Pom has “representative works” such as “Making the Sky of Hiroshima. ‘PIKA!'” and “LEVEL 7 feat. ‘Myth of Tomorrow'” that have (intentionally or unintentionally) caused a stir in society. However, I felt that it’s this “Street” that can be called Chim↑Pom’s representative work, in terms of its simplicity and vividness.

With such a tremendous exhibit from the very beginning of the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition,” I felt as if I had been hit over the head with a sledgehammer. This “Street” can be said to be the trigger that refocuses attention on the existence of “Chim↑Pom,” which I had hardly known before.

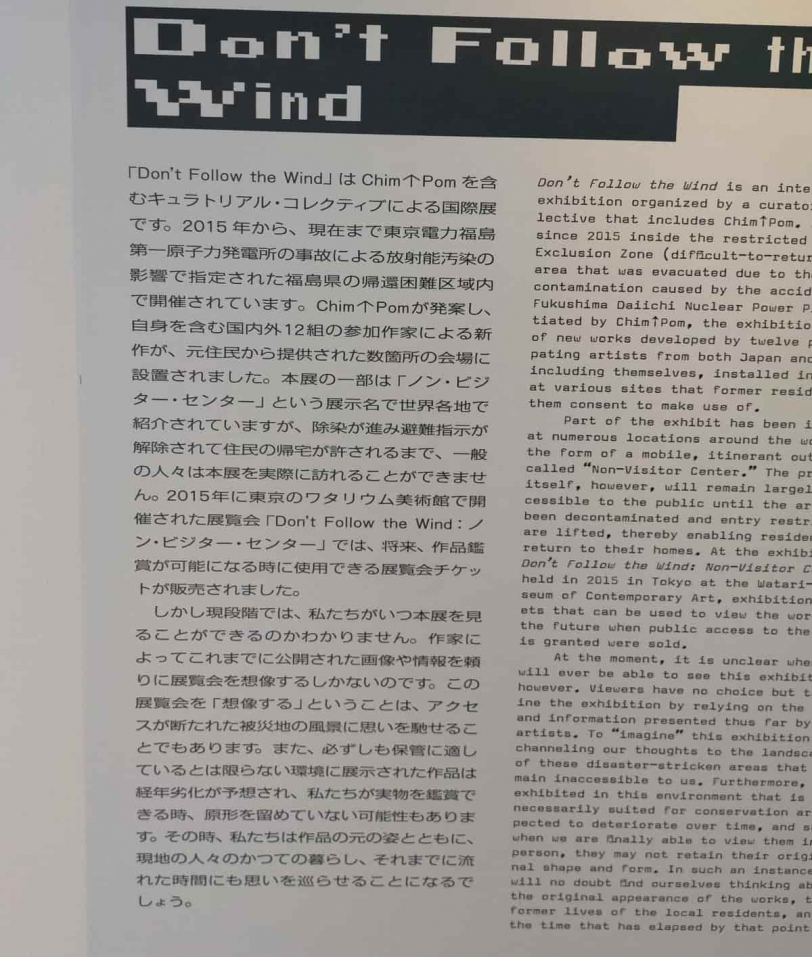

The Impact of “Don’t Follow the Wind” Exhibition in Difficult-to-Return Zones

After the footing part of the construction site, the exhibition of “Don’t Follow the Wind” begins. However, this is not an accurate expression. More accurately, what is being exhibited is the introduction of the exhibition of “Don’t Follow the Wind”.

I know it is hard to understand what I am talking about, but adding the information that “it is done in Difficult-to-return zones in Fukushima Prefecture” would make it all the more understandable.

First, let me explain a bit more about the “Introduction to the Exhibition of ‘Don’t Follow the Wind'” that was on display at the Mori Art Museum. In this exhibition room, there is only one laptop placed, and on the wall, there is a brief overview of “Don’t Follow the Wind” and a looped audio playing in the background. There is no photo or caption related to the artwork, just an empty space.

The audio includes recordings of exchanges between Chim↑Pom and several members involved in “Don’t Follow the Wind”, as well as residents who provided their homes in the Difficult-to-Return zones for the exhibition. The audio explains how the exhibition of “Don’t Follow the Wind” is presented and the current situation, but it’s hard to imagine the specific artworks.

This is the “complete picture of the exhibition inside the Mori Art Museum.” I was impressed by the “impactful exhibition that vividly conveys the meaning of ‘Don’t Follow the Wind’ through the absence of any physical artwork in the exhibition room.”

First, let me briefly explain about the exhibition of “Don’t Follow the Wind” that is being displayed at the Mori Art Museum, quoting from the article in “Bijutsutecho”.

“Don’t Follow the Wind” is an art exhibition that uses sites and buildings owned by local residents who support the concept of the project as its venues. Due to strict access restrictions, it is difficult for visitors to actually visit, making it essentially an “unseeable exhibition.”

Four years after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Accident, on March 11, 2015, “Don’t Follow the Wind” (hereinafter, DFW) started. It is an art exhibition planned by Chim↑Pom, held in areas designated as Difficult-to-Return zones due to radioactive contamination.

This is an extraordinary “art exhibition” that makes us feel amazed at the idea and realization of such a thing.

The most impressive part of the audio that was playing was when the residents who provided their homes for the exhibition were talking about “deciding to dismantle their homes.” Naturally, along with the dismantling, the exhibits were also lost, making it impossible to see them anymore. We will only be able to see this exhibition after the designation of Difficult-to-Return zones is lifted, but at that point, we won’t know what has become of this exhibition. And that is precisely the crux of “Don’t Follow the Wind.” An interview article with Eva & Franco Mattes, one of the participants in the curation of this exhibition, states as follows:

”For Mattes, who has been focusing on the ethical and moral issues arising from online communication for many years, this point was important. ‘For the organizers, going to difficult-to-reach places, meeting local people, gathering information and confirming facts, and holding an exhibition in a place where a major disaster occurred, were all meaningful aspects of this exhibition.’ Not posting photos of the exhibition easily on the internet became an important concept in itself. ‘I think most of the audience will experience this exhibition indirectly through word of mouth, and there are some photos of the exhibition circulating online, but it cannot accurately convey the actual situation on-site.’ In the deserted site, nature erodes, and the exhibits are constantly exposed to change. There have been cases where wild boars have broken through the doors of houses and destroyed the artworks”. (Eva & Franco Mattes)

At the Mori Art Museum exhibition, displaying photos of the artworks would have been possible, of course. However, the true essence of “Don’t Follow the Wind” lies in the fact that we cannot see it, and that the exhibits decay while being unseen. It is, in a sense, an antithesis to modern society where everything, including art, is constantly “consumed”.

”The biggest feature and challenge of this exhibition was that the audience could not see it. For at least the first few years, there was a problem of how to convey this exhibition in a situation where the audience could not come. ‘We had to provide information, but at the same time, we were worried that if we provided too much, the exhibition would be consumed too quickly. Today, online tools such as video conferences are essential for planning and preparation of exhibitions. However, with the increasing prevalence of onlineization, it seems that the act of spreading photos of exhibitions on social media itself is becoming the purpose’.” (Eva & Franco Mattes).

The message of “not showing” is made clear while maintaining a compelling necessity to not show. Furthermore, there is also this intention behind “Don’t Follow the Wind.”

”The motivation behind the project was to pull artists, curators, and even the audience out of their “safe zone”. We wanted to reexamine everything that is normally taken for granted, including safety, at typical art events”. (Eva & Franco Mattes)

It can be said that it completely deviates from the framework of “existing art”. I felt it had an incredible imagination.

The preparation for this exhibition seems to have been quite difficult. First of all, the difficulty of “entering and working in the Difficult-to-Return zones” becomes apparent.

Mattes has visited Fukushima several times for exhibition preparation, but obtaining permission to enter the Difficult-to-Return zones was not easy. Even if they were able to enter the area, there was no electricity, water, toilets, or food, and they could only stay for a maximum of 5 hours at a time.

Furthermore, on top of that, they had to face a special difficulty that is unimaginable in a normal art exhibition.

As the exhibition venue, 4 houses lent by the residents were used. The space was the opposite of a sterile and characterless “white cube”. “In the venue where radioactive contamination was a concern, furniture, clothes, photos, books, and other personal memories were scattered. We were very careful during installation to exhibit the works without compromising the feelings of the owners.”

However, it seems that there was also joy during the preparation stage.

”It might sound insensitive, but thanks to one of the locals, we actually had a really good time in the area. He took us out for drinks, fed us delicious food, and entertained us with singing and jokes. He really went out of his way to treat us well. I think he didn’t want to be seen as a ‘poor victim’ of the disaster. He showed us that even in the most miserable circumstances, you can still enjoy life to the fullest, and his spirit really moved us”. (Eva & Franco Mattes)

I feel that there is a certain “necessity” in the process of Chim↑Pom’s work, which enhances the meaning of their actions. And it is precisely because of this sense of “necessity” that the people involved with Chim↑Pom would also treat them differently from the way they treat “artists. I especially realized this after reading various descriptions in “Bijutsutecho” magazine. Chim↑Pom has chosen “physicality” as one of their themes, which means that their works do not exist simply as “artworks”, but are organically connected to something else, deepening their meaning. It can be said that this ability to create such “connections” is what makes Chim↑Pom unique.

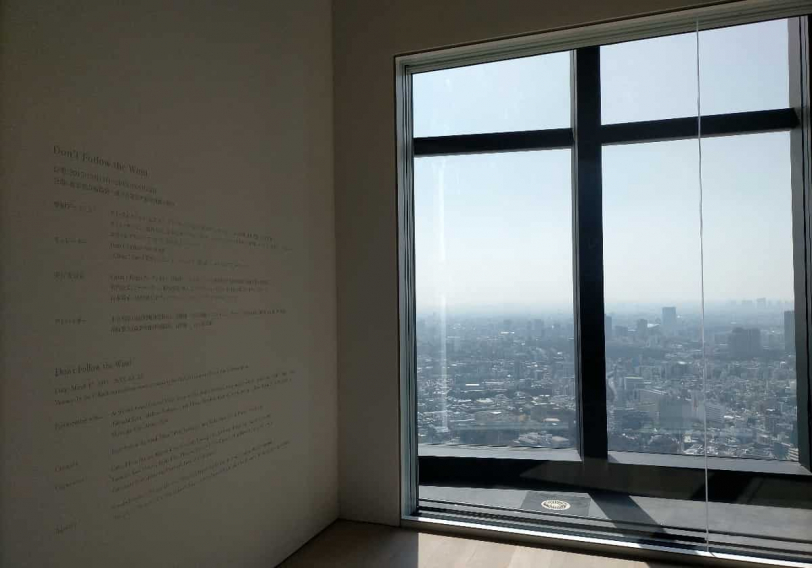

Let’s go back to talking about the “Don’t Follow the Wind” exhibition at the Mori Art Museum. There is another characteristic of this exhibition. It is held in a exhibition room where we can overlook the city of Tokyo from the window.

As previously mentioned, this exhibition is intentionally created as a very empty space with only one computer placed in it. Additionally, the art exhibition being introduced there is one that cannot be seen in reality, but clearly imagines a town that would be “devastated”.

On the other hand, an exhibition that emphasizes such keywords as “emptiness” and “devastation” is being held in the “space within a metropolis” of the 53rd floor of Roppongi Hills, a “metropolis within a metropolis”. Moreover, we can overlook the cityscape of Tokyo, the metropolis, from there.

This “too bleak contrast” was also very impressive. Although it was not specifically mentioned in the Mori Art Museum or “Bijutsutecho,” this contrast is clearly intentional. In a “city where everything is too present, where development has reached its limit,” the experience of viewing (or imagining) an “exhibition that is being held in a ‘town where everything is too absent, where everything is decaying'” is like being confronted with indescribable questions. I was also impressed by the idea of evoking such a feeling by “exhibiting” a “mere space where nothing exists.

What Chim↑Pom Thought about the “Mori Art Museum” Exhibition

Besides the two points introduced so far, there are various other exhibitions, which will be introduced later in the form of “Chim↑Pom’s past projects”. Here, based on the description in “Bijutsutecho”, I would like to touch on how Chim↑Pom perceives the “Happy Spring” Exhibition at the Mori Art Museum.

They have taken various themes related to “city” and “public” in the past, and they were also considering exhibiting at the “Mori Art Museum” in the city of Roppongi. However, it seems that they couldn’t quite get on the same page with the Mori Art Museum. Regarding this point, Ushiro Ryuta said the following in a dialogue with Odawara Nodoka:

Ushiro: “We talked about how the ‘city’ of Roppongi Hills and the ‘city’ we are thinking about while doing projects in Kabukicho are different. The public nature of Mori Building’s urban theory and our urban theory is different. When we talked about it, they said, ‘There is no public nature in Mori Building’s urban theory.’ I had always felt a gap, but I thought, ‘Ah, this is it!’ They only have a city as a brand, and they are not necessarily thinking about the public.”

Odawara: “That’s why Chim↑Pom would be approached. To transmit values different from our own from the museum. That is why we use it too.”

I’m not confident if I understand this statement correctly, but I think Mori Art Museum doesn’t recognize themselves as a “public space,” and that’s why Chim↑Pom, who is considering the “public nature of each public space,” couldn’t quite communicate with them.

Just on this point, there would have been no problem with holding the exhibition. Whether or not the Mori Art Museum recognizes itself as a “public space,” the museum can be objectively recognized as a “public space,” so Chim↑Pom only needs to consider “what to do within the public nature of Mori Art Museum.”

However, there were other practical problems. About that point, Chim↑Pom’s Hayashi Yasutaka said the following in comparison to the Taiwanese museum’s “Street” exhibition.

”Looking back, negotiating in Taiwan was difficult, but I think it was easy to understand. In other words, because the standards were based on law and art, we were able to share the rules. However, this time there were unexpected constraints such as the condition of being on the top floor of a tall building and the logic of the corporation as standards”. (Chim↑Pom Hayashi)

When they visualized the “difference in publicness between ‘public roads’ and ‘art museums'” at a museum in Taiwan, it was only necessary to consider “whether it meets legal requirements” and “whether it is art.” Therefore, it means that while it was hard, it was not difficult because of its simplicity. However, when exhibiting at the Mori Art Museum, there were conditions such as “exhibiting on the top floor of the building” and “private corporate ethical regulations” that had to be cleared. So it was not simple at all, which is the point being made here.

And a problem arose where Ushiro Ryuta showed his dissatisfaction by boycotting all meetings for about a month, indicating that he was not satisfied.

In Chim↑Pom’s early work, there is a project called “SUPER RAT” that catches rats in Shibuya, moreover there is also a work called “Pikachu version of ‘SUPER RAT'” that replaces the rat with “Pikachu”. However, the exhibition of this “Pikachu version of ‘SUPER RAT'” was rejected. Let’s quote Ushiro’s statement about the situation.

”Because the feature of Chim↑Pom including of PARCO is that they enhance the limits of certain facilities and institutions each other. The reason for this is that the exhibition of “Pikachu version of ‘SUPER RAT'” in the art museum was rejected. At first, the art museum tried their best to make the exhibition possible, but as an organization, the art museum is also a part of the Mori Building, and ultimately, the exhibition was reluctantly moved outside the museum out of consideration for the copyright holder of the design used in the work. The first alternative proposed by the museum was to show it in the second venue. They took the stance of protecting freedom of expression and the right to know by changing the ‘way of presentation,’ but I initially refused it as censorship and boycotted all meetings for about a month. However, the art museum’s efforts for about a year were substantial, and there were differing opinions among experts on copyright law, so it seemed that there were no obvious problems with exhibiting the work. Even so, it eventually reached the point where even yellow rats in videos on the 53rd floor were not allowed, and even the entire exhibition was in danger. We understood from lengthy dialogue that they were also very regretful about the final decision. If so, we can make use of the accumulation that we have made up to that point. As artists, we believe that our freedom of expression has been undermined, but we have conversely suggested that we should develop a project to explore how art institutions can have independence and autonomy in the future, in collaboration with the museum, at the second venue where “SUPER RAT” has been driven away. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

I went to the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” without researching it in detail and ended up not being able to see “Venue 2”. At the end of the Mori Art Museum exhibition, there was a guide about “Venue 2”, but without reading it carefully, I thought, “If there is a Venue 2, let’s go on a different day,” and went back. Later, I found out that I couldn’t enter “Venue 2” if you do not make a reservation on the day I saw the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition,” which is why I couldn’t see the “Pikachu version of ‘SUPER RAT’.” It’s a shame.

So, Chim↑Pom was fighting against various “rules” that the Mori Art Museum had.

Additionally, the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” has a “street” made of asphalt. I want you to see it in person to understand where and how it exists, but only minimal exhibits are placed on this “street.” There is also intent behind this.

For Chim↑Pom, who has worked in the streets and slums and has focused on urban development, there is a Site-Specific necessity to bring their own construction to the art museum operated by a major developer. Additionally, there are various events planned to occur on the “street” during the exhibition period. “Just laying asphalt doesn’t make it a street; ‘nurture the street’ work is necessary,” says Hayashi. Bold projects that utilize the context of the location and methods that combine artwork displays with events are Chim↑Pom’s specialty.

Through experiencing various projects that Chim↑Pom has carried out, I think I have a vague understanding of the idea of “nurture the street,” even though I’ve never naturally thought of it myself. It probably means that “street” is not a “substance” but a “phenomenon.” This can be inferred from Ellie’s comment during her conversation with Ueno Chiduko.

Ueno Chiduko: “I have a prejudice against contemporary art. Contemporary art is conceptual art, and conceptual art is linguistic. As a sociologist, I am a person who is very biased towards language, so I think that if art does not do what language cannot achieve, it is not art. “What are you doing art for, show me something that can only be expressed non-verbally?” So when I saw the “Happy Spring” exhibition, I thought it was fundamentally different from the “feminism” exhibition in terms of physicality and locality.”

Ellie: “Chim↑Pom’s strength of ‘first taking action’ has been learned through the body. We’re not placing any works on top of ‘street’ in this exhibit because we want to hold events there during the exhibition period. It’s about using the interest of being alive and in the present moment.”

Ueno Chiduko’s review of the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” is interesting, but Ellie’s discussion of “physicality” is also intriguing. By organically generating “place/space” and “phenomena” simultaneously, they elevate these things into “art” or “raising social issues.” It’s like feeling the brilliance of the technique.

Ellie talks about exhibiting at the Mori Art Museum like this:

”After doing it this time, I realized that the reason why it becomes like “Holding a solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum is out of fashion” is because the artist is swallowed up by the other artist. It means that the exhibition starts and ends without the artist being able to demonstrate his or her true nature. But this time, we were able to do it with confidence. So, when this exhibition is over, I don’t think it will be so different from usual.” (Chim↑Pom Ellie)

I first learned about even the assertion that “Holding a solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum is out of fashion,” but it’s probably based on the idea that “if it becomes well-known in society, it will just be consumed, and the Mori Art Museum is the embodiment of that”. However, if I liken it to the claim of “nurture the way,” I can say that the projects that Chim↑Pom undertakes “grow by being known by many people. I feel that their unique method of blending “artistic quality” and “social issues” in an exquisite balance becomes even more distinct when exposed to the gaze of others.

Regarding this point, there is an interesting mention in “Bijutsutecho.” Wakui Tomohito, who runs the community “WHITE HOUSE” with Ushiro Ryuta, made a statement.

“It is important to get non-members imagine what is happening in the enclosed space. Moreover, it is important for members to recognize that such a perspective exists externally. It is in such a space where maturity can occur because it is a gathering place for such people. In recent years, there have been a lot of ‘easy open, let’s have a dialogue’ types of people, and I think we have a lot to lose because of that. If we try to communicate to all kinds of people, it simply becomes an ‘opportunity to explain’.” (Wakui Tomohito)

In response to this, Ushiro says,

“The phenomenon of works being closed off occurs when we think too much about making them easy for anyone to understand and opening them up.” (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

The discussion about “opening/closing” is also mentioned several times in “Bijutsutecho,” which is interesting, but I will touch on that later.

The exhibition at the Mori Art Museum is never “closed off” per se, but I think it has in common of the point of “recognizing the presence of the gaze,” and the point that “maturity” can be possible to encourage by that gaze. It’s also true that “maturity” can be fostered through that gaze. Chim↑Pom’s works and projects are bound to spark discussions, and by being subjected to a wider gaze, they should shed even more light on “social issues” and create a situation where discussions lead to more discussions.

Personally, I feel that this is very “healthy”.

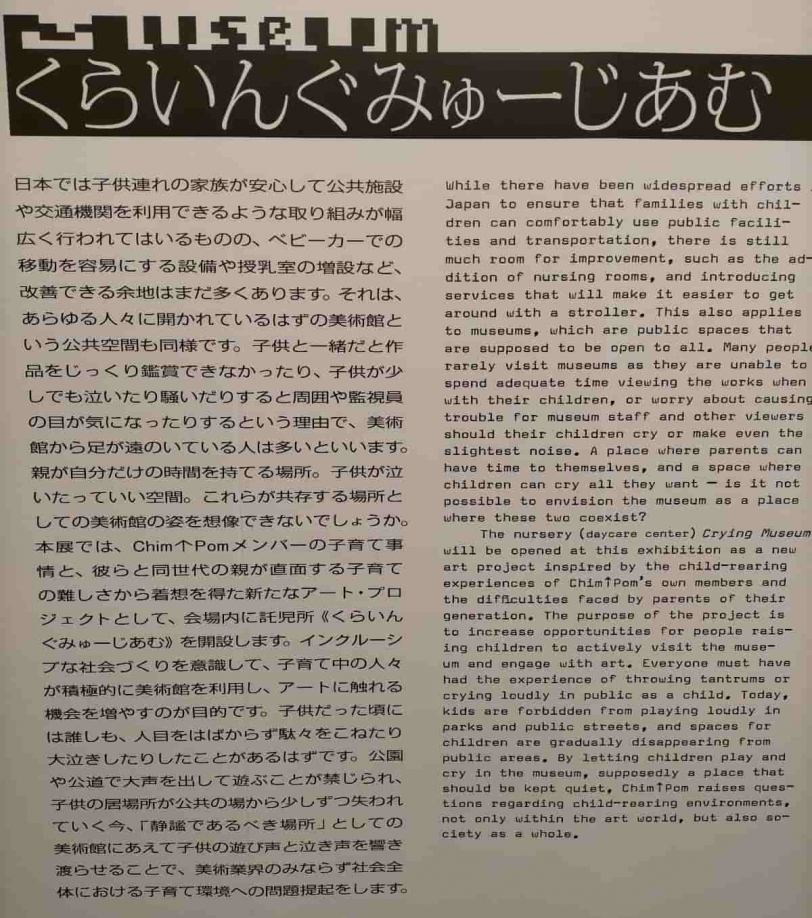

Let me end this section by mentioning that the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” at Mori Art Museum was very impressive even before I passed through the entrance. A “nursery” was set up at the entrance. The nursery is also named “Crying Museum,” and in a sense, it is part of the exhibition.

This daycare center/exhibit is a good example of Chim↑Pom’s style, and it helps solve the difficulties that people with children face when entering public spaces. It can be said that it also challenges the conventional idea that museums should be quiet and serene.

Chim↑Pom Talks about “Public”

Let’s take a break from talking about the Mori Art Museum exhibition and dig deeper into Chim↑Pom’s frequent theme of “public.” First, let’s touch on the dialogue about “public” held in “Bijutsutecho,” and then introduce various projects that Chim↑Pom has carried out so far, touching on the perspective of “public.”

About the Dialogue “Questioning ‘Public’ and Art” in “Bijutsutecho”

A dialogue about “public” is recorded in “Bijutsutecho.” It is by Ushiro Ryuta of Chim↑Pom, who has co-authored the book “公の時代(Public Era),” and artist Odawara Nodoka, who has created and written on the theme of “public sculpture.”

The dialogue discusses the “meaning of art existing in public spaces” and the “non-democratic selection process of art placed in public spaces,” among other topics related to the relationship between “public” and “art”. It is a content that clarifies the essence of “public.”

Now, I’d like to highlight the most essential and straightforward statement that came up in this discussion. Ushiro Ryuta introduced a statement that Ellie made in the past, and I felt it hit the nail on the head.

“When we were interviewed about ‘LEVEL 7 feat. ‘Myth of Tomorrow’ (2011),’ Ellie said, ‘Myth of Tomorrow’ is mine.’ I felt that it was one ultimate answer to the question of who the public belongs to, and the way of interpreting public art fundamentally intersects with the example of BLM”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

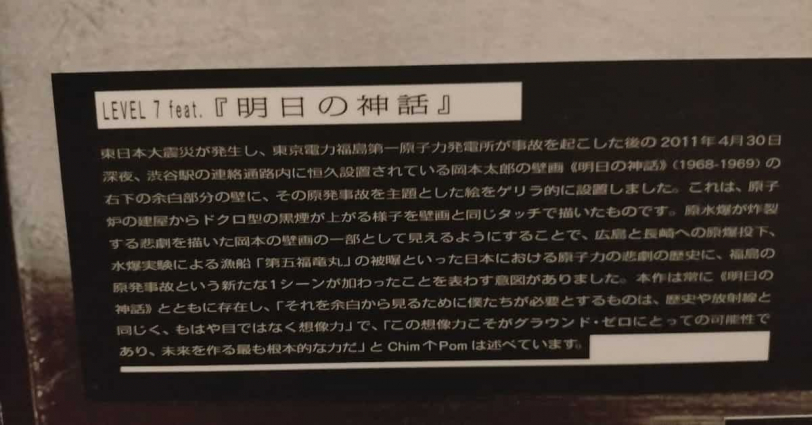

To understand Ellie’s statement “’Myth of Tomorrow’ is mine” correctly, let’s first take a look at Chim↑Pom’s work, “LEVEL 7 feat. ‘Myth of Tomorrow.'”

There is a huge painting called “Myth of Tomorrow” by Okamoto Taro displayed at Shibuya Station. The painting’s background includes issues such as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Daigo Fukuryu Maru hydrogen bomb incident. I didn’t know about these facts before. Here’s a link to the Taro Okamoto Memorial Museum, where you can see what kind of artwork it is.

-1024x682.jpg)

On the wall where this painting is displayed, there is a blank space in the lower right corner. On April 30th, 2011, Chim↑Pom illegally pasted a painting of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident onto this blank space so that it could connect seamlessly with “Myth of Tomorrow”. This pasted painting is referred to as “LEVEL 7 feat.’Myth of Tomorrow'”. The painting was removed the next day and it even led to a criminal case.

About the reaction of the public at the time, “Bijutsutecho” wrote the following.

The incident where an artwork was added to Okamoto Taro’s “Myth of Tomorrow” (1969) at Shibuya Station in 2011 was widely discussed, including in the mass media and among the general public. While many in the art world were positive about this act of expression, especially during a time when many people were questioning the power of culture and the arts in the face of the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Tokyo Electric Power Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Accident. By connecting the Fukushima disaster to Okamoto Taro’s work, Chim↑Pom created a brilliant method that could only be done by them to update Japan’s nuclear history in a public space. Mizuno Tasuku, the lawyer who handled the criminal defense when the installation of the artwork was prosecuted as a criminal case, also felt the same way, saying, “When I learned of the incident, like everyone else, I didn’t know who had done it, but I thought it was a critical expression for Japan at that time.”

I vaguely remember this uproar, but at the time I think I had a feeling similar to “a brilliant trick.” Now in 2022, learning about “LEVEL 7 feat.’Myth of Tomorrow'” again, I feel it’s “genius.” Ueno Chiduko, who had a conversation with Ellie in “Bijutsutecho,” was impressed, including projects like Chim↑Pom’s famous “Making the Sky of Hiroshima. ‘PIKA!'”, saying things like:

”For example, works about Hiroshima and Fukushima made me think ‘how could anyone come up with something like this’?”(Ueno Chiduko)

I felt the same way. Even if one knew that “Okamoto Taro’s paintings were located at Shibuya Station” and that “it depicted the history of the atomic bombing and radiation exposure,” to launch a guerrilla-style “LEVEL 7 feat. of Tomorrow” immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake would be not something that one would normally think of. In terms of simplicity and vividness, I feel like it’s on par with the “Street” at the museum in Taiwan, and in terms of having a critical impact on society, isn’t it at the top?

Now, Chim↑Pom’s act was considered a violation of the Minor Offenses Act and they were referred for prosecution. An interview with Mizuno Tasuku, the lawyer who represented Chim↑Pom at the time, is featured in “Bijutsutecho”. He said the following:

However, these minor offenses are crimes that incur a fine of less than 10,000 yen per person and less than 30 days of detention, so it was possible to pay the fine and end the matter. At first, I told them to just pay the fine and be done with it. The lawyer’s fees would be more expensive, haha. But they believed in the legitimacy of their act and wanted to argue that it was an expression of art. So, we decided to submit a statement to the prosecutor’s office arguing the effects of the criminal act on freedom of expression and art, while listening to the details of the act and the intention behind the work. We aimed for a non-prosecution decision.

Mizuno Tasuku, who himself had experience in art, created a 47-page statement explaining that Chim↑Pom’s act did not violate the law and submitted it. “I honestly don’t know if this statement helped or not,” he said. However, as a result, Chim↑Pom was not prosecuted. I think it was really great that Chim↑Pom fought without paying the fine and didn’t receive the judgment of the law.

In a discussion about Chim↑Pom, Mizuno Tasuku said,

Actually, my impression of them hasn’t changed since I first met them. They are more serious than their image suggests and always discuss every possibility in detail. They are very prepared. In fact, from the very first discussion, they said, “The goal is for this painting to be collected by the Taro Okamoto Memorial Museum.” And it really happened! They’re not necessarily refined in terms of “strategy,” but they have a prophetic quality.

Yes, Chim↑Pom’s “LEVEL 7 feat. ‘Myth of Tomorrow'” caused a lot of controversy, but as a result, it was collected by the Taro Okamoto Memorial Museum. I think it’s remarkable and shows that Chim↑Pom’s actions were recognized as correct.

It may have been long, but this is what lies behind Ellie’s statement “’Myth of Tomorrow’ is mine”. In other words, “The Okamoto Taro painting displayed in the public space of Shibuya Station belongs to everyone, so it’s also mine.”

I don’t think this is the only solution to “public,” but at least you should be able to understand the claim that “it cannot be considered incorrect.” It should exist as one perspective of “public.”

Now, during the interview, Ushiro Ryuta said the following:

”In Japan today, the relationship between the public and the individual has become numb”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

Taking into account the context leading up to this statement, this can be understood as meaning of “being losing of breadth of the perception of ‘public’.” Ushiro Ryuta and Odawara Nodoka believe that there should be a variety of answers to the question of “why art exists in public spaces” and that various actions should be allowed in response. For example, they imagine situations where sculptures may be destroyed or damaged, but they take the following stance:

”Accepting such situations is a meaning of having works in public spaces. If there is a necessity, we should overwrite them as much as possible. I’m prepared for criticism, but I think it’s the most brilliant state. It’s okay to always be in a state of tension with the system or management”. (Odawara Nodoka)

Of course, the philosophy behind the “LEVEL 7 feat. ‘Myth of Tomorrow'” project, which was carried out in a guerrilla-like manner, is also included in this.

The discussion assumes that “public” and “art” have been in a state of tension, but that tension no longer exists. There are various reasons for this, but in the discussion, issues related to “consensus formation” and “historicization” are pointed out.

”When creating a monument, questions are raised about who will use what money from what standpoint and under what pretext. Whether it’s public or private, using personal funds or public funds, a certain consensus must be formed and events must be historicized in order to create a monument. In terms of historicization, numerous monuments have been created in the ten years since the earthquake, but I feel that it is too early”. (Odawara Nodoka)

”Regarding Upopoy, I read Odawara-san’s review and felt that it was the opposite of Tsuyama’s story. It seems that the museum has made the past disappear. As mentioned in ‘公の時代(Public Era),’ the fact that Japan has no museums of aggression means that for Japanese people, the war is not over in a sense. Hiroshima and Nagasaki can look to the future with a focus on learning from the past through the presence of museums, but we still can’t even grasp the history of aggression, not even in the present”. ( Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

Ushiro Ryuta gives an example that is the opposite of public sculpture, and it is the “Tsuyama massacre” that appears in the quotation as “Tsuyama’s story”.

”A few years ago, I went to Tsuyama in Okayama Prefecture, where the ‘Tsuyama massacre’ happened.(omission)When I got there, I thought, ‘This is an event without a monument’.”(Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

To summarize Ushiro Ryuta’s point, “building a monument” is an act of “putting an event in the past,” but the case does not yet past. The only thing placed on the grave of the perpetrator who caused the incident is a round stone picked up from a river by their relatives, out of consideration for the feelings of the victims. The “MURAHACHIBU (village ostracism)” continues to this day due to the incident that occurred in 1938. Therefore, it is impossible to “create a monument to make the past event,” and that is what the “Tsuyama massacre” is all about.

And it is pointed out that something like that might be the role that “art” was originally intended to play.

”It’s easy to be summed up easily by administrative leadership, isn’t it? If a single stone like Tsuyama that naturally emerged can convey the true feelings for the incident, rather than a top-down monument, the need to symbolize like a work of art itself would be shaken to its very foundations”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

Before thinking about “what to place,” the act of “placing something there” itself creates meaning. He understands that if he doesn’t correctly capture that meaning, only the message based on “what to place” will be left floating, and ultimately nothing will be conveyed.

”Japan is a place with many disasters, so it would be better if there were more discussions on what kind of monuments are appropriate and why they should be replaced by sculptures. However, such discussions are rarely heard”. (Odawara Nodoka)

And in the midst of this conversation, Ushiro Ryuta makes the following statement:

”In a lecture where Beuys spoke about the sculptor Wilhelm Lehmbruck, he said that sculpture is ‘a measure for measuring measure.’ This means that by placing objects in space, the space becomes visible”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

This argument overlaps with what I felt when I saw the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” at the Mori Art Museum, so I’d like to explain it a little, even though it’s a bit off-topic.

When I saw the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition,” I felt that by placing a donut in an empty space, a space with the meaning of “donut hole” was created. The part we call the “donut hole” would return to an “empty space” if there were no donut. The “donut hole” is completely dependent on the existence of the “donut” and cannot be visualized without it.

And I felt that the relationship between “Chim↑Pom’s art” and “social issues” was very close to this.

We live in what is called “society” and are naturally “connected” to “social issues” in it all the time. However, when we live in “society”, we may feel that our environment is “normal” and may not feel the sense of being “connected to social issues”. It’s like the “difference in publicness between ‘public roads’ and ‘art museums'” presented by the Taiwanese museum’s “Street”. It existed in front of us even before the exhibition of “Street”, but it was not in our sight.

However, Chim↑Pom presents some kind of art there. That is a “donut”. As a result, “social problems (the hole of the donut)” are visualized. This is exactly the presence and role of “Chim↑Pom’s art”. It is also similar to the feeling of “placing things in space to make space visible” that was quoted earlier.

“Art in public spaces” should also have the same role, but various functional disorders, including decision-making processes, prevent it from displaying its presence correctly.

That’s why Ushiro Ryuta says the following:

”In today’s Japan, the relationship between public and private is paralyzed. In such a situation, it is better to operate and practice something like public rather than intervening in public as an individual”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

This change of viewpoint can also be said to be very brilliant.

In regards to “operating and practicing something like public” that Ushiro Ryuta mentioned, I want to introduce an interesting story that I happened to hear. In a movie I watched before, there was a description of a street drama called “Jinriki Hikouki Solomon” performed by Terayama Shuji’s theater company “Tenjo Sajiki.”

It was extremely fascinating.

Terayama Shuji conducted a street drama called “Jinriki Hikouki Solomon” in an actual city area as the name suggests. He expressed the public space where the play was performed as a “nation” in a very impactful way, saying “1 meter square 1 hour nation.”

The drama started from a 1 meter square and doubled its “territory” every hour. The play itself is performed for over 12 hours, so the “territory” becomes quite large by the end.

During the press conference for “Jinriki Hikouki Solomon,” Terayama Shuji said, “As the ‘territory’ expands, there may be situations such as a car parked inside the ‘territory.’ But since it is our ‘territory,’ we may even break that car during the flow of the play.”

I found this to be an amazing story. I don’t know if there was actually a scene where they destroyed a car parked within the “territory.” However, it’s surprising enough that Terayama Shuji suggested such a possibility. The person who parked the car recognizes that place as just a “public space,” but in a different layer, it is the “territory” of Tenjo Sajiki’s play. The reasoning may be absurd, but if I deliberately take this claim at face value, it means that “multiple publicities overlap” here. It can be said that this is a situation similar to the “Street” in a museum in Taiwan.

I’m not sure how much overlap there is with Ushiro Ryuta’s “operating a public,” but I think Terayama Shuji’s play can also be considered a form of “operating a public.” It was a very interesting conversation.

One of the keywords for Ushiro Ryuta’s “operating a public” would be “open/close”. He mentioned this point in the context of “Holding a solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum is out of fashion”, and also made the following statement in this interview:

“In recent years, everyone is conscious of ‘opening’, but I think there are many things that become impossible because of it. Generally, by being considerate and self-regulating, we end up with results that are only showing a ‘closed public’, giving a sense of discomfort. I had this feeling.” (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

I can understand this feeling very well, not only in the context of art, but also in more familiar examples. For instance, the text that appears on TV variety shows, such as “The staff ate the food deliciously later” (a display intended to appeal that the food is not being treated poorly in a food-related segment), which is shown as a matter of course. I even feel a perverted sense of calling the environment where creation cannot be carried out without “avoiding criticism beforehand” as “public”.

Perhaps there is more potential in an “unconstrained ‘closed public'” than a “constrained ‘open public'”. Ushiro Ryuta probably thinks so too, and if he were to run a “public”, that stance would likely be incorporated.

Ushiro Ryuta, including the already quoted passages, draws on Uchida Tatsuru’s ideas about “publics” and argues.

”Uchida Tatsuru pointed out that in the West, there is a concept that public property is property. Everyone limits their private rights and gradually pools their property together, which creates a sense of stakeholder awareness. On the other hand, in Japan, public property is perceived as something that is just there, like the wilderness or the sea. So people use it, but there is no stakeholder awareness. When I read that, I thought that if public were like the wilderness or the sea, then there might be potential. The problem is how to operate it”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

I think “operating a public” will become one of Chim↑Pom’s themes from now on.

Various Other Projects Chim↑Pom has Done So Far

Here, I would like to touch upon various arts and projects that Chim↑Pom has produced so far, besides what has been introduced before. While being aware of the theme of “public,” I intend to discuss even those aspects that are not related to it.

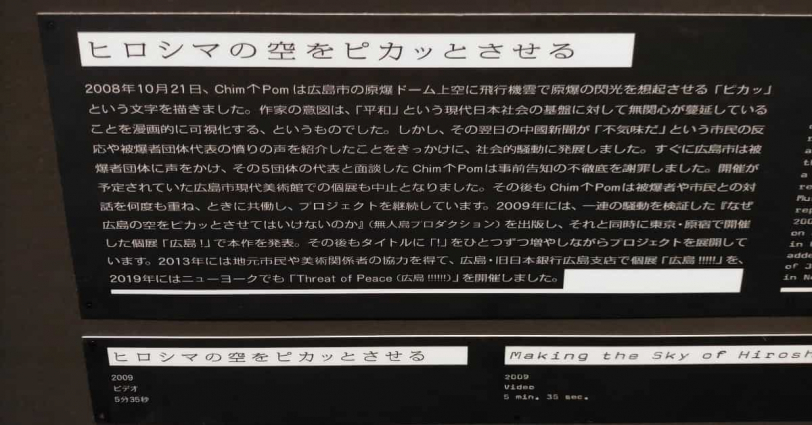

Speaking of Chim↑Pom, their work “Making the Sky of Hiroshima. ‘PIKA!'” is famous. Even before I saw the “Chim↑Pom Exhibition” at the Mori Art Museum, I had some knowledge of Chim↑Pom because of this work. This was a project in 2008 to draw the character “PIKA!” in the sky of Hiroshima with contrail. As you can easily imagine, they faced considerable criticism at the time.

However, Aida Makoto, who could be considered Chim↑Pom’s mentor, spoke of how they faced the people of Hiroshima, as follows.

”Chim↑Pom faced the people of Hiroshima with impressive perseverance after the large uproar caused by ‘PIKA!’ in particular.” (Aida Makoto)

Due to the bashing, their solo exhibition scheduled to be held at the Museum Studio of Hiroshima MOCA was canceled. However, they did not give up there.

Chim↑Pom, who did not let the bashing get to them, visited a number of hibakusha organizations and continued dialogue with them, and ended up not only reconciling with them, but also getting their support.

Thus, “Hiroshima! Project,” which could be considered Chim↑Pom’s life’s work, began. They left the latest footprints in the lineage of atomic bomb art.

This was quite a tremendous accomplishment. At the Mori Art Museum, a chronology of how Chim↑Pom responded to criticism and backlash was displayed, conveying that it was not something half-hearted. However, they conveyed their enthusiasm for “hoping you see the work and understand the true meaning” and were able to start a new “Hiroshima! Project.”

Matsunami Sizuka, a gallery staff member who was involved as organizer in the “Hiroshima! Project” gallery staff, answered in an interview.

Chim↑Pom’s “The Peace Day” series (2011/13), which was created locally in Hiroshima, was sold in various places in the city where it was well received, and the sales were used as exhibition funds at the Former Bank of Japan. “The Peace Day” is a group of several hundred works, each consisting of a painting on panels of various sizes, ignited by “atomic bomb embers,” and composed of soot and other materials. “Many people in Hiroshima bought them. At the time of the ‘Preparation exhibition!’, there seemed to be more people interested than angry.”

Furthermore, the “Hiroshima! Project” even made its way to the United States, the country that dropped the atomic bomb, and “made a splash in the New York art scene.” Despite facing harsh criticism that even reached those outside the art world, Chim↑Pom’s incredible project showed their determination and eventually led them to New York.

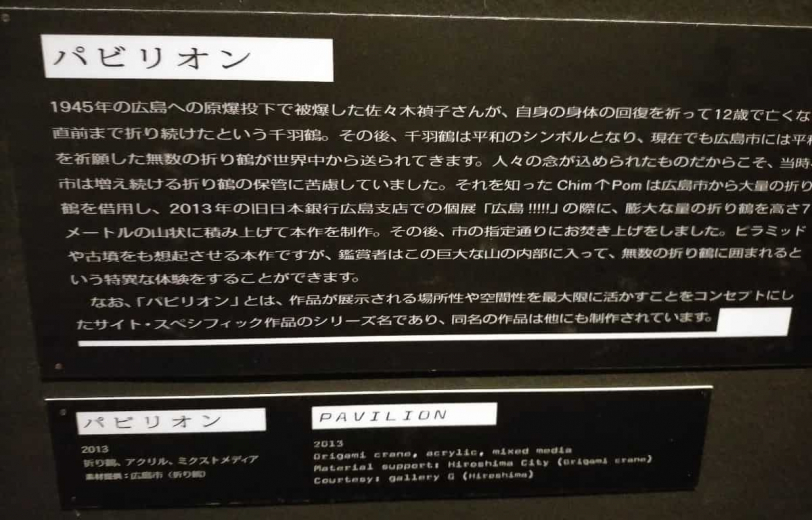

In the “Hiroshima! Project,” there was an exhibit called “PAVILION,” which was created by forming a dome-shaped structure using a large number of Thousand Paper Cranes borrowed from Hiroshima City, reaching a height of 7 meters. The episode surrounding the paper cranes is also wonderful.

Ueno Chiduko: “Who came up with the ‘idea to use paper cranes sent from all over Japan’?”

Ellie: “We talked to locals in Hiroshima and felt their emotions. Then we suggested, ‘Let’s all go see it together.’ We are usually refused, but that’s already a big assumption, so we negotiate.”

Ueno Chiduko: “Your negotiation skills are amazing. Although some people would know how to preserve the paper cranes, using them for art is an unprecedented idea. You have an incredible ability to involve and communicate with people.”

Chim↑Pom learned that Hiroshima city was struggling with the storage of paper cranes sent from all over Japan. So, they came up with an idea to use these paper cranes for art and after negotiations, they made it happen.

In addition, they started a project where “they would unfold the paper cranes, turn them back into origami and fold them into the paper cranes again,” proposing that “making folding paper cranes ongoing process, while not increasing the total number of paper cranes.” At the Mori Art Museum exhibit, there was a box with square paper with folding creases from paper cranes, and a sign that says, “Please fold paper cranes freely with this paper.”

I also wanted to fold one, but unfortunately, I completely forgot how to fold a crane and gave up. I was surprised that I forgot how to fold a crane, but regardless, I feel that this brilliant idea is amazing in showcasing the value of art in society.

The “So see you again tomorrow, too?” project held in Shinjuku in 2016 was reportedly an unconventional scale. A whole building scheduled for demolition was used, with the central part of floors 1 through 4 being hollowed out. The debris, along with furniture, were placed on the first floor like a monument. Exhibits were displayed in various forms over a two-week period, and events were held for two days. Komuro Tetsuya also participated in the event. Eventually, the building was demolished along with the exhibits.

Teduka Maki, who runs host clubs in Kabukicho, was deeply involved in organizing this event. It was thanks to him that Chim↑Pom was able to use this building for their exhibition. However, the preparation process was reportedly quite difficult.

According to Teduka, the road to realizing the exhibition was far from smooth. “At first, the significance of contemporary art was not understood,” he says. “The union members often say, ‘We can coexist, but we cannot live symbiotically.’ As a non-profit organization, there were no people who strongly supported or opposed holding the exhibition. It was like talking to a wall. However, Sugiyama Motoshige, who was the executive director at the time, was supportive of the project and took charge of negotiations within the organization. Eventually, we were able to clear the Fire Service Act and persuade the union members and the building demolition company.”

”During the event, I often talked to the policeman so that I would not be warned. I thought it was my role to finish this event without incident,” recalls Tezuka.

The theme of this event is the “town/city” itself, rather than the “public”. This is a “Shinjuku-specific approach” that is typical of Chim↑Pom, which has been involved in various projects in each city, such as the SUPER RAT in Shibuya and an exhibition in Roppongi Hills.

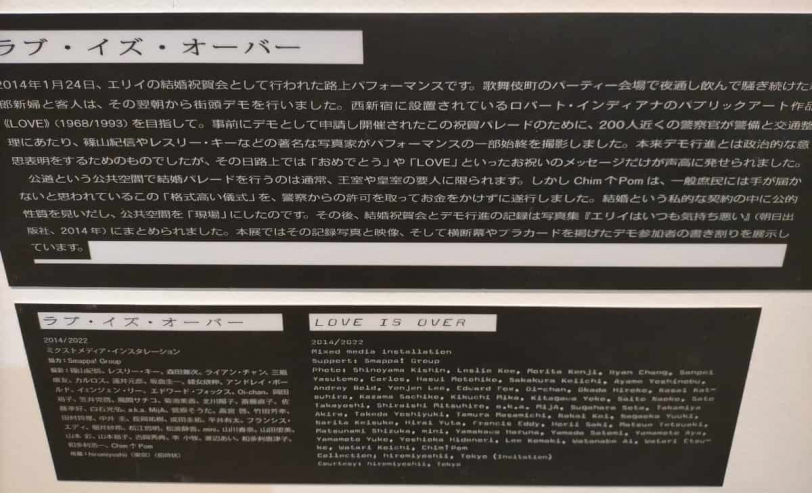

Teduka Maki and Chim↑Pom’s relationship actually goes back further. Ellie’s husband is Teduka Maki, and in 2014, Chim↑Pom performed “LOVE IS OVER” under the guise of a “wedding demonstration”. Although the idea is simple, it was a stunning event that probably no one had thought of before.

After Ellie and Teduka Maki’s wedding party, they conducted a “street demonstration”. They applied for permission from the police in advance and walked from Kabukicho in Shinjuku to Robert Indiana’s public art “LOVE” in Nishi-Shinjuku, conducting a “demonstration march”. However, the only things that were asserted in the demonstration were “LOVE” and “congratulations”. In other words, it was a “marriage party in a public space under the name of a demonstration”. They were able to do something that would normally cost a lot of money for free, with just a notification to the police.

The scene at that time was captured by a famous photographer and later published as a photo book called “エリイはいつも気持ち悪い(Ellie is always in weird).”

Teduka Maki had this to say about Ellie’s state during “So see you again tomorrow, too?” period.

“Ellie said every day during the exhibition period, ‘I can’t sleep thinking about what would happen if someone fell and died in the hole.’ She said she dreams of people dying even when she sleeps. Of course, we took every precaution to ensure that no accidents occurred. But when I heard that story, I thought, ‘Oh, they’re really serious about this.'”(Teduka Maki)

To be honest, I was surprised by this story as well. I thought I understood that they were serious about art after seeing the exhibition at the Mori Art Museum. However, I think there was still a part of me that was looking at it with a somewhat playful image. I think Teduka Maki, who felt, “Oh, they’re really serious about this,” probably has had a similar impression. That’s why I was somewhat surprised to see Ellie taking the fear of someone dying at the event seriously. Knowing this episode, I feel like I can understand their seriousness even better.

Now, such “So see you again tomorrow, too?” is seamlessly connected to another project. At the “Sukurappu ando Birudo Project Road Opens Up” exhibition held at the “Kita-Kore Building” in Koenji, a “paved road” made using the debris of a Kabukicho building was laid down. This private road, named “Chim↑Pom Street”, was opened to the public like a regular road and had various exhibition pieces scattered throughout. Public restrooms and crime prevention cameras were also installed.

Initially, there seemed to be only a vague idea of “doing something at Kita-Kore Building using the debris of buildings in Kabukicho,” but after various discussions involving organizer and architect Suo Takashi, it evolved into the following plan.

”One idea that emerged to solve these problems all at once was to create a ‘street’ within the Kita-Kore site. It’s an idea where a part of the broken city is brought to a different place and becomes the place itself”. (Suo Takashi)

The idea of “street” did not come about suddenly, but was born from the following process.

Chim↑Pom members listened to the history of the Kita-Kore structure from the surrounding residents. “(Omission) We found out that there was originally a private road on the Kita-Kore site. It was decided to revive it and connect it to a public road. (Omission) If we use urban debris such as the Promotion Association Building there, it will be a case of “using the foundation of the broken city to create a new urban public space”…. and the dots of meaning were connected by a line.” (Suo Takashi)

It can be said that Chim↑Pom’s approach is to make the most of the background of each location.

Furthermore, Suo mentioned the following:

Aside from using materials brought from Kabukicho, we also needed to create a “place” through the street, which led to the idea of “nurture the street”.

As you can imagine, this concept of “nurture the street” that emerged at the “Sukurappu ando Birudo Project Road Opens Up” exhibition led to the creation of “Street” at a museum in Taiwan later on. Thus, Chim↑Pom’s projects can find various organic connections even among different projects.

Suo himself, who was involved with Chim↑Pom, has his own ideas about “public” and says the following.

If we can create a place itself, we can question the public nature of the city. Suo believes that a street is an infrastructure, the topography itself, including the surrounding buildings, and that the individuality of the topography influences the behavior of the people in that place.

“I feel that we Japanese have a mentality that public spaces are ‘we are allowed to use’. I think we can express a different way of being in a place where each individual can be involved in the public space as a party.”

In this way, it can be said that being able to work with organizers and projects that resonate with Chim↑Pom’s stance is their strength and characteristic.

Now, let’s return to Shinjuku. In 2018, it was decided to demolish a building in Shinjuku again, and since Teduka Maki was renting the building, an event called “Ningen Restaurant” was held for two weeks before the demolition. According to Matsuda Osamu, an artist involved in the event, the event was so chaotic that no one could fully grasp who was doing what, as he stated:

”I don’t think anyone has a complete grasp of the whole event. However, there is no mistake that I know the most about it. This is because I was at the venue for 10 days straight”. (Matsuda Osamu)

The concept was “various physical performances and living organism exhibitions around human potential,” and during the event, it transformed like a living organism, incorporating immediately the frequent suicides by jumping from buildings in Kabukicho that had nothing to do with the event.

“Ningen Restaurant” had a clear awareness of “public” issues.

In the first place, the background to the concept of “Ningen Restaurant” was Chim↑Pom’s discomfort with the “public” concept they had at the time. As Matsuda explains in the co-authored book “公の時代(Public Era)” (Asahi Press, 2019), this discomfort has two basic aspects. One is discomfort with the way urban space is being redeveloped for the Tokyo Olympics. For example, recent parks have become “majority” places aimed at the majority, rather than “public” places open to everyone, and individual diversity has been excluded. Another question was the question of art in which the “extreme individual” aspect of the artist is disregarded because the work is used in an “illustrative” way in the story envisioned by the curator. In looking at the current state of language-based art where curation is the main character, Chim↑Pom questions whether “is that what artists are?” As an antithesis to the era where “public” is emphasized over “individual,” the aim here is to present the bare “Ningen (human).”

If I had actually seen the event at “Ningen Restaurant” with my own eyes, I’m not sure if I could have imagined this kind of background, but when it’s explained in words, it makes a lot of sense. Indeed, while using the word “diversity,” there are often cases where I feel like saying, “The ‘diversity’ you speak of does not include ‘people like XX,’ does it?” Even though “any individual” should be accepted, I often feel uncomfortable when a “specific individual” is unconsciously excluded. And I find the idea of counterposing something artistic as the antithesis of this very interesting.

And,The fact that Chim↑Pom and Matsuda Osamu planned “Ningen Restaurant” with the following in mind can also be seen as a form of “running a public” as described by Ushiro Ryuta.

We do not want to create a place for art that is managed top-down under a certain philosophy, but to create a bottom-up place where a large number of people gather and no one is able to grasp the entirety of what is happening.

As mentioned earlier, Ushiro Ryuta had a sense of discomfort towards “constrained ‘open public'”, and had an image of “unconstrained ‘closed public'” as to that, but I think that this “Ningen Restaurant” can be expressed as the opposite, a “public that is too open to be constrained”. In any case, I felt that it was a difference in operation methods of “how to remove constraints”, and that the goals were the same.

The project called “A Drunk Pandemic” is also a very interesting project. Let me introduce it by quoting from an article in “Bijutsutecho”.

A brewery was set up in the underground ruins of the Manchester Victoria station, where people who died of cholera during the Industrial Revolution were buried. The beer brewed there was then served at a bar called “Pub Pandemic” outside the tunnel, which was connected by the sewer system. The sewage from the toilet in the bar was then used to make bricks in a factory called the “Piss Building” inside the tunnel.

It may seem really strange and mysterious how such an idea came about, but there is actually some inevitability to it. During the cholera epidemic, boiled beer was considered safer than untreated water, which inspired this project.

”I think Chim↑Pom is always a presence that visualizes local elements. The ‘Piss Brick’ with mixed audience urine was a controversial idea, but was precisely a representation of the theme that we were discussed”. (Grainne Flynn)

Grainne Flynn, who was involved in curating this exhibition, says, “Piss Bricks” with “C↑P” written on them are actually used in a building in the Northern Quarter. Chim↑Pom’s works are indeed eroding society beyond the framework of art.

He also says the following:

”Chim↑Pom is active in showing a deep interest in the community and history of the region in any location”.(Grainne Flynn)

It can be said that they understand accurately the core of Chim↑Pom.

However, the idea of “making bricks with urine that was produced after drinking beer” is still abnormal. I felt that this project demonstrated Chim↑Pom’s style of not hesitating to create controversy if it embodies the theme.

Finally, let me introduce “KI-AI 100” to end. It was exhibited at the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition and Its Aftermath” of a project in the “Aichi Triennale”, and I didn’t know, but it seems that it caused quite a controversy.

“KI-AI 100” is a work like the following.

In May 2011, a video was made in which young people who met in Soma City, Fukushima Prefecture, which was a disaster area in the Great East Japan Earthquake, formed a circle and cheered to themselves 100 times in a row.

The video was also shown at the Mori Art Museum, but even after thinking back on its contents, I didn’t really understand why it caused a controversy. I hadn’t watched the entire video, so I finally understood it after reading the description in “Bijutsutecho”.

”Personally, I really disliked that ‘KI-AI 100’ got flamed. In that work, there is a cry from local children in Fukushima saying ‘Radiation exposure is wonderful!’ The responsibility for those words being labeled as ‘anti-Fukushima sentiment’ lies with us, doesn’t it? It was painful to think about them”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

I understood, but it’s still strange. What’s wrong with the fact that children in Fukushima who have actually experienced the disaster say “Radiation exposure is wonderful!”? Of course, I also think it would be a problem if someone who is not a victim and has no connection to Fukushima said the same thing. However, the statement was made by those directly involved. To me, it feels more appropriate to listen to Inaoka Motomu from Chim↑Pom, who said the following:

”In both ‘KI-AI 100’ and ‘Making the Sky of Hiroshima. “PIKA!”’, the people involved are trying to move forward by digesting their own experiences, which is why they might say ‘do more.’ However, people from different generations or places tend to be overly protective of them. When the ‘Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition’ was cancelled, I worked at Takayama Akira’s ‘J Art Call Center’ and handled complaints from people who called in. At that time, I talked to people who called ‘KI-AI 100’ ‘anti-Fukushima sentiment.’ I argued, ‘The people who were affected by the disaster couldn’t express their feelings properly at that moment, so they had to say that. Is it still considered hate?’ But I felt like we could never fully understand each other”. (Chim↑Pom Inaoka)

It’s natural to have differing opinions on Chim↑Pom’s methods, and I think that’s healthy. However, objectively comparing “Chim↑Pom, which is directly involved in social issues in Hiroshima and Fukushima” and “an anonymous individual who probably hasn’t done anything specifically for Hiroshima or Fukushima” ought to definitely favor Chim↑Pom. But in society, there are times when “hypocrisy wearing the mask of ‘justice'” is supported.

I feel that such a situation is very unhealthy. With Chim↑Pom, I hope they can ignore such meaningless criticism and push forward on the path they believe is “right”, while stirring up both support and opposition.

What is “Chim↑Pom”?

Chim↑Pom is an art group that was formed in 2005 and is now celebrating its 17th year. It consists of six members: Ushiro Ryuta, Hayashi Yasutaka, Ellie, Okada Masataka, Inaoka Motomu, and Mizuno Toshinori, and has continued without changing its members since its formation. Except for Ellie, none of them graduated from art school, and they are a rather unique group made up of members gathered under the artist and former teacher at a school of aesthetics, Aida Makoto.

From here I would like to touch upon such Chim↑Pom while citing various words mentioned in “Bijutsutecho”. In the following, I will write an article dividing it into “Chim↑Pom as a whole” and “Ellie as an individual”. Ellie’s presence is so central to Chim↑Pom that it can be said to be the axis, so I would like to mention her separately.

About Chim↑Pom as a Whole

“I think Ushiro said something light like, “Aida-san, we’ve decided to form our own group. It was in 2005, at my old house in Nishiogikubo, in the living room of an old single-family house. ‘Hmm, well, do your best.’ I think I was in that kind of mood too. It’s better to try something than to do nothing, so it was just that kind of reaction on a usual sluggish (probably Sunday) morning when I heard Ushiro’s report on the formation of Chim↑Pom”.(Aida Makoto)

Aida Makoto, known as the mentor of Chim↑Pom, wrote like this. When they first formed, Aida Makoto’ only thought to the extent of that it was better to try something than to do nothing. However, he soon changed his mind like this:

“I wanted to quickly throw Chim↑Pom, whose leader, Ushiro, is a high school dropout and overall a non-art school graduate, into the old-fashioned art college world.”(Aida Makoto)

He thought so after seeing the first work of Chim↑Pom, titled “ERIGERO,” which was presented in 2005 and featured Ellie just vomiting pink vomit. As expected of Aida Makoto. The Mori Art Museum also shows the video of “ERIGERO.” If you watch the video after reading the explanation, certainly we can understand that it has conteined “social criticism.” However, I think that if you only watch the video, you will feel like “what the heck is this?”

However, at the same time, I felt that “Chim↑Pom-likeness” that also leads to the current appearance is certainly condensed in “ERIGERO”.

Aida Makoto says he has never given advice to Chim↑Pom, but he always follows their movements and describes their progress as follows:

“It’s like they suddenly took on a high-difficulty off-road challenge without a license, smashed up the car, and polished their special driving technique.”(Aida Makoto)

I think “without a license” means that many of them didn’t graduate from art college, and “smashing up the car” perfectly captures the Chim↑Pom-like quality of sometimes causing controversy while continuing to show their presence.

The magazine “Bijutsutecho” includes comments from organizers who have been involved with Chim↑Pom in various ways, describing how they perceive them. Many of them view the group as having a sense of unity despite not having individual harmony, saying things like,

“Sometimes I feel that they are getting along very bad, and at other times I feel that they are actually very concerned about each other, and can appear like siblings. Although each member is strongly individualistic, when they come together as a group, there is something like a single personality called Chim↑Pom, which is kind of mysterious.” (Matsunami Sizuka)

”Chim↑Pom consists of six individuals with distinct personalities who typically keep to themselves. However, when creating works or projects, they act as catalysts for one another, accelerating each other’s reactions. Through the production process, I felt a common element of Chim↑Pom’s sincerity towards art”. (Suo Takashi)

Ellie also commented as follows:

”I think this is what society is about because we are collaborating with people who we would never have interacted with if it weren’t for Chim↑Pom”. (Chim↑Pom Ellie)

I believe this would mean that they have no overlapping characteristics as individuals. However, when the six of them come together, the personality of “Chim↑Pom” is manifested.

Chim↑Pom’s unique feature is that it consists of six fixed members for over 15 years. While they pursue individual activities such as curation, writing, and TV appearances, they always have a collective authorship when creating works. They explore each other’s ideas and desires, exchange opinions, and create a “small society” within the six members. I think this creates the diversity of perspectives and dynamics in their works.

Chim↑Pom has been holding weekly meetings called “Chim↑Pom meeting” since its formation. They share their opinions on what to create and how to create it, and decide on the direction in these meetings.

Hayashi Yasutaka spoke about this meeting as follows.

”Concepts are important, but works that can be explained in words are boring. The balance between the part that can be understood in words and the sense of creating something tangible is important. if we are doing tug of war without being biased one way or the other, we can create something crooked that we don’t even understand ourselves. That might be what the Chim↑Pom meeting is all about, pulling in opposite directions and creating something that’s unique to ourselves”. (Chim↑Pom Hayashi)

In addition, Inaoka Motomu says this.

”It’s a given that everyone doesn’t have cohesion, and without Ushiro-kun to suck up everyone’s opinions and put them together, we’re all over the place. That’s why even if he says he ‘quit being the leader,’ it doesn’t matter. Chim↑Pom without Ushiro-kun is not Chim↑Pom”. (Chim↑Pom Inaoka)

Originally, Ushiro Ryuta was the leader of Chim↑Pom, but it seems that he suddenly decided to “quit being the leader,” so currently there is no “leader.”

Chim↑Pom, who is practically anyway but ostensibly leaderless, is in the situation like this.

”Since Chim↑Pom didn’t start with a strong common direction, they have many internal disputes”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

On the other hand, they also feel like this:

”But sometimes, Chim↑Pom’s needs and the activities each member wants to do don’t align. Actually, it’s not interesting if they don’t deviate. In the end, I felt deciding on a vision doesn’t mean anything, let’s stop worrying about everything.” (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

It can be said that this is what makes them interesting.

At their first meeting of the year in 2019, they confirmed a common understanding:

“’Chim↑Pom probably doesn’t have a vision or a unified goal, or even shared hobbies.’ ‘It would be great that each Chim↑Pom image will emerge from their individual activities.’ If we are going to continue, I hope it will”. (Chim↑Pom Ushiro)

I think it’s because of that stance that they create an atmosphere as follow.

”I like that they don’t just create works that only make sense in the context of art, but rather use art forms to talk about society, politics, and philosophy in an improvisational way. Also, I like that their lives are always reflected in their works, and that there is a relationship where their works and lives interact with each other”. (Betty Apple)

In the interview between Ellie and Ueno Chiduko, the keyword “mutual-aid association” may also represent Chim↑Pom’s uniqueness.

Ueno Chiduko: “So it’s been going well for 17 years. Even in bands, people quit or want to go independent, and there’s turnover.”

Ellie: “Maybe it’s because everyone is easygoing. And also, none of us really have any motivation (haha). We struggle along with the six of us, barely alive. But there is a feeling of ‘If we’re going to do it anyway, let’s live by doing something interesting and moving.’ Being Chim↑Pom might be one of the most fun and easy ways to live.”

Ueno Chiduko: “Interesting! So it’s a mutual-aid association.”

To be honest, I envy having peers who share such feelings.